December 18, 2017

Climate change is creating unpredictable risks for local and national governments around the world – a fact that gained new urgency after this year’s devastating hurricane season. But how can cities and countries be prepared for what they can’t foresee?

Leaders and experts from across the New York and New Jersey region joined Bloomberg LIVE to answer that question at The Future of Resilient Design, focusing on the innovative ways the region responded to 2012’s Superstorm Sandy – an ongoing process that is being closely observed by vulnerable communities worldwide.

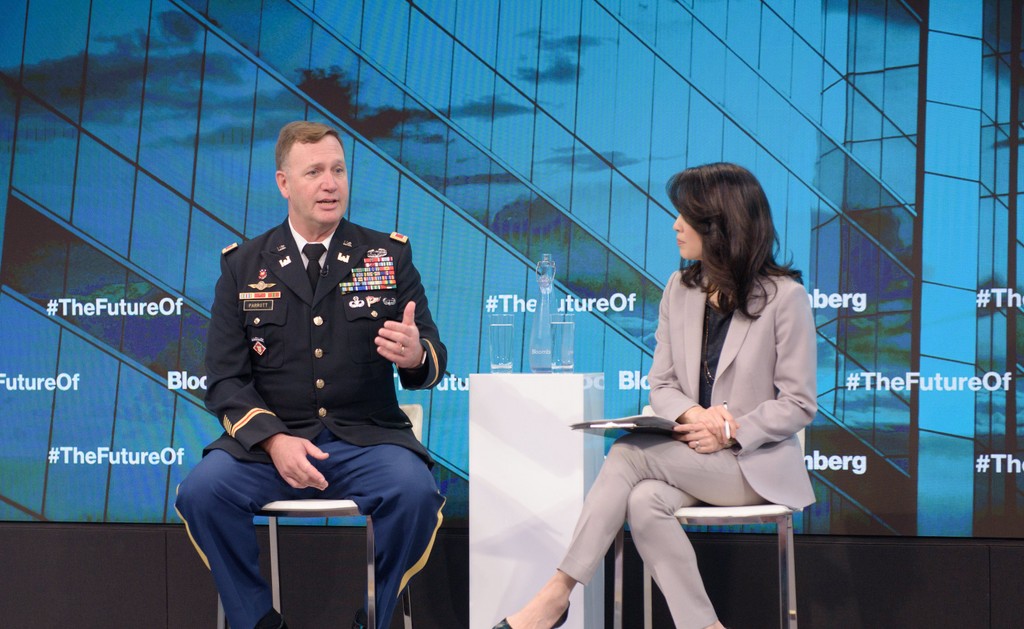

Speakers included public leaders like Colonel Leon F. Parrott of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Mayor Dawn Zimmer of Hoboken, NJ, Daniel A. Zarrilli, Senior Director of Climate Policy and Programs and Chief Resilience Officer for the New York City Office of the Mayor, and former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie, as well as utility and transportation officials including Con Edison Chief Engineer Luciano N. Villani, New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority COO Phil Eng.

Industry experts Janice Barnes, Global Resilience Director and Principal, Perkins + Will, and Greta Byrum, Director of Resilient Communities for New America Institute, provided perspective on recovery efforts. Bloomberg Television and Radio Anchor Scarlet Fu and Bloomberg Associates Principal, Sustainability Adam Freed guided the insightful conversations.

The Future of Resilient Design event continued a future-focused series supported by Siemens, a global leader in automation and digitization. Siemens President, Digital Grid Michael Carlson welcomed the group, noting that it was after Superstorm Sandy that the term “resilient” entered the national conversation and became a priority across business, industry and government.

Highlights from the event provide a fascinating snapshot of the innovative work that’s helping make that a reality.

New risks require broader thinking

Superstorm Sandy was the worst natural disaster New York City has ever experienced, said Mayoral office resilience expert Daniel Zarrilli. “It changed how we think about risk in New York City,” he said; but “one positive that came out of it was a broader thinking about the risks we face.”

That goes beyond simply rebuilding or preparing for the next Sandy-like storm. Forecasts aren’t always accurate – and heat can be as devastating as flooding. “Heat kills more people globally each year than all other natural hazards combined,” noted Bloomberg Associates’ Adam Freed.

“It’s about thinking in a much more flexible way about what could happen next,” added Greta Byrum of New America institute.

Building for resiliency

An example comes from the way that Consolidated Edison rebuilt power stations following Sandy. The utility company came up with a new standard that went beyond protecting against a similar event, said Chief Engineer Luciano Villani. That meant that many more stations than those directly affected by the storm were included in restoration work after Sandy.

Such policies protect against not knowing what the next emergency will be. New America Institute’s Byrum enumerated three resilient principles that can do the same for all infrastructure: “it should be modular, it should be flexible, and it should be distributed,” she said.

The principle of flexibility applies to more than infrastructure itself, added Janice Barnes of design firm Perkins + Will. Effectively building for resiliency needs to work across traditional boundaries and ways of doing things. “If you don’t look at other perspectives, your ability to respond professionally with a systemic understanding is reduced. If we could see more broadly across disciplines, we would be much better off,” she said.

Communities play a powerful role

Local areas may be vulnerable to weather events – but they also have other needs, such as job training or access to broadband connection. Resilient infrastructure solutions that take those needs into account can also help to build a stronger social fabric, or even train people to be the workforce of the future.

For example, structural engineers now work with community activists to help monitor local infrastructure in some areas, Barnes said. That makes both people and constructions safer and more resilient in the event of an emergency.

Mayor Dawn Zimmer of Hoboken emphasized the need to include communities in infrastructure planning. “You can have the funding, you can have the engineering – but if you don’t have the support on the community level, you’re not getting the project done,” she said.

Eighty percent of Hoboken was under water following Sandy, she noted – including fire stations, electrical stations and hospitals. Even before Sandy hit, the city was vulnerable to flash flooding; water management had been a key priority. But, Zimmer said, “you can’t just build walls. It has to be something with co-benefits.” A flood barrier that’s also a park protects residents – and also provides a day-to-day amenity.

Leadership matters

New York’s Zarrilli agreed, pointing to the Rockaway Boardwalk as an example of this kind of resiliency planning. More than five miles of boardwalk were replaced at Rockaway Beach, built with sustainable materials and planted dunes to reinforce resiliency. “You don’t even realize the protection is there,” Zarrilli said.

New York’s leadership – in both infrastructure planning and its commitment to the Paris Agreement – is being watched around the world and across the US. Colonel Leon Parrott of the US Army Corps of Engineers noted that “the majority of the US population is either in an urban area or within 50 miles of the coast. In any of those areas, there’s not a lot of room to make changes.”

Advance planning can make a vital difference. In one example, Phil Eng of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Authority said the decision to suspend subway service and send trains to protected yards ahead of Sandy helped prevent even more damage from happening.

But leadership “is only half making decisions,” said former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie. “The other half is conveying the decisions and being compassionate.”

When faced with the unprecedented, Christie offered this advice: “Take a deep breath; ask lots of questions; measure twice and cut once.”

Read Next:

The Future of Innovation: Spotlight on Artificial Intelligence